THREE STORIES

ONE

We gave Scott until the end of the month to pack his things and get out. No more negotiations. No more excuses. If he wanted to kill himself he should do it on his drug dealer’s time. Ma and I spent nights arguing about the plan, and she gave me an earful about parental encumbrance, but I put my foot down and we finally decided that I would do the speaking and she would support.

He flung a million and a half expletives at us, and his sister, but he got it. He left that night. We left the room as-is and put our focus on Jeannie. So when he knocked on our door one evening, a few months later, I had to muster all the callousness left in me to say, “Yeah, what do you want?”

He broke into tears, making a scene at the doorstep, going on and on about finally quitting.

He was staying at a homeless shelter that had a reputed rehabilitation program. He had just officially started sobriety a day before and asked if he could temporarily visit. Not to sleep, he insisted, just share a meal and feel supported. Ma didn’t even look at me before she hugged him into the house with her “of course my dearie of course.” And that’s how we started “Sober Dinners.”

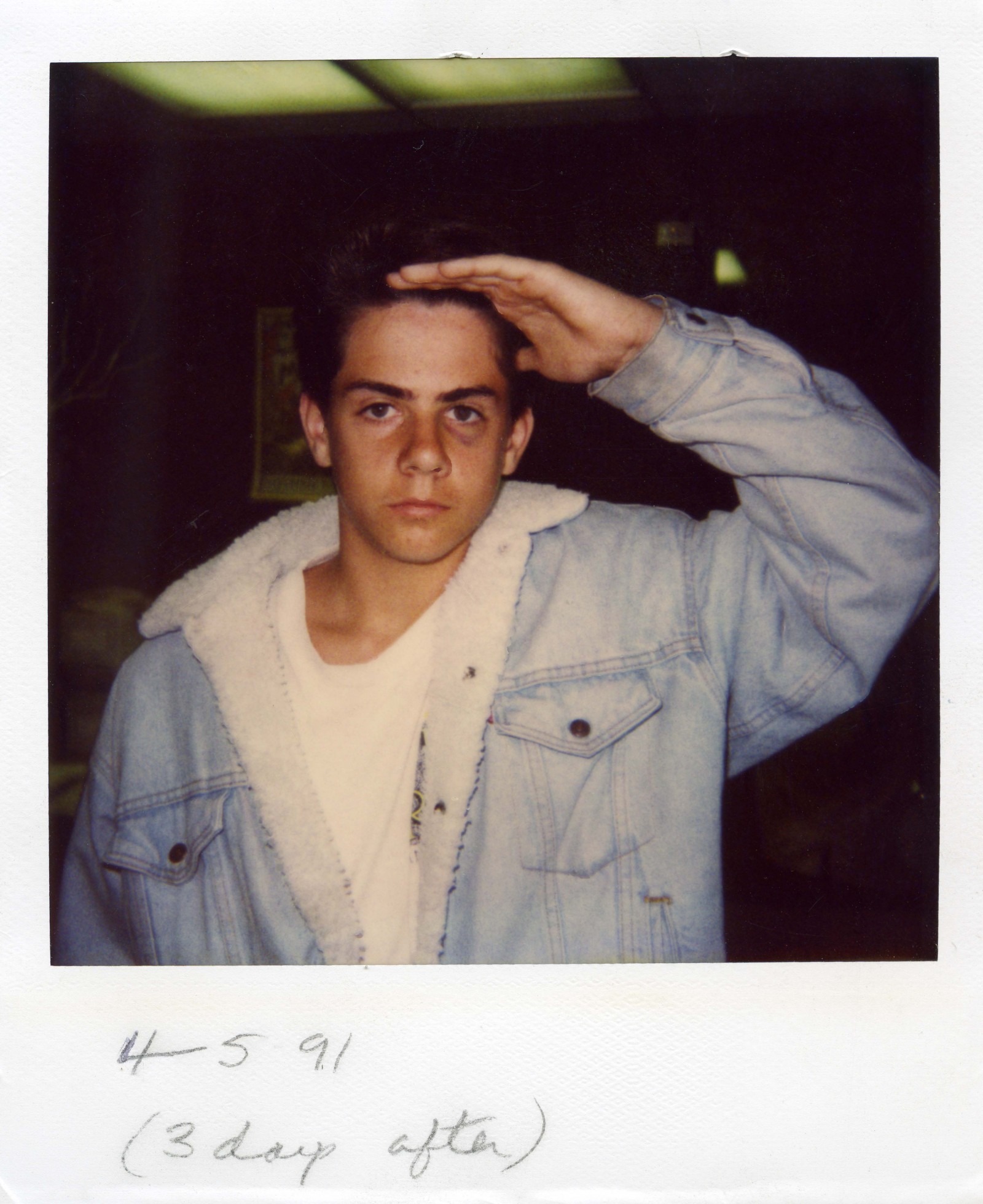

The next day I took a picture of him for the progress. Ma felt his marks unseemly, so I lent him my jacket and he understood. I remember he said he was “reporting for duty.” Dinner was civil. The television was going on all day about the plane crash in Georgia—the one with the senator on it—and witnesses were filling in the gaps. They were still letting the families know about it before they’d reveal the names.

That’s about as much as I can remember. Anyhow, I kept it—the picture—to show him who it was we believed in if he ever started slipping again. This guy right here. This guy right here.

We were proud of Scotty. I wished he knew that.

Story by Leonard Stein

TWO

I said, “Don’t talk to my little sister like that ever again.” It was a warm morning in June, the last day of school, actually. I was enjoying the peanut butter and jelly sandwich that my mom packed me— the last brown paper bag lunch I would have since I was going off to college in the fall. It was always the same things in my lunch. Sandwich. Chips. Fruit. Dessert. Juice box. On important days she would throw a note in there to wish me good luck on a game, or words of encouragement to get me through a test. As I took the final bite of my sandwich I noticed my little sister, a sophomore, being harassed by a guy in my grade.

I gathered my things, threw out my brown paper bag, and walked briskly over to her. Greg, the guy talking to her, was making snarky comments about what she was wearing that day. I said, “Don’t talk to my little sister like that ever again”. But he ignored me and kept running his mouth. I couldn’t take it anymore and threw the first punch. It hit him right in the ear, and after he realized what I just did, I knew I had made a mistake. This 6 foot 3, 250 pound guy was about to make me pay for what I just did. He looked me in the eyes, drew back his arm, and socked me square in the eye, sending me to the ground.

I walked home feeling defeated, but my little sister reminded me what I did for her. The guy never spoke a word to her again, and I had a nice shiner on my left eye to show for it. My black eye stayed there for a whole week; I was proud of it. I did my job as a big brother, I was a man.

Story by Paige Haley

THREE

Blame it on Holden Caulfield. Or Jack Kerouac. Or maybe you could blame it on the fact that no one gave a damn about me until I ran away. Whatever the case, three days ago, I came to the decision that my old life just wasn’t doing it for me. Stuffing a backpack with a few changes of clothes, my toothbrush, some food, my “life savings,” and my copies of “Catcher in the Rye” and “On the Road,” I left home and decided I’d start life anew as a wanderer. Though I look pretty small for my age, I could take care of myself. Unfortunately, in those few days, I didn’t manage to make it very far, mostly because I realized no one was really willing to let a kid hitchhike with them. Then, about a half hour ago, the local authorities and my parents finally managed to catch up with me. They found me in a hotel lobby a mere three counties away. Of course, my family made a big show of looking relieved. My mom was crying and wouldn’t stop hugging me. My dad, in an impassioned frenzy, snapped this photo “as a reminder,” he put it, that I’d learned my lesson. Now, as I sulk in the backseat of my dad’s car, watching the glow of the streetlights pass outside the window, they’re as silent as statues. But mark my words, I’m already planning my next escape. And this time, I’ll be sure that they won’t ever find me.

Story by Chester Sakamoto