four STORIES

ONE

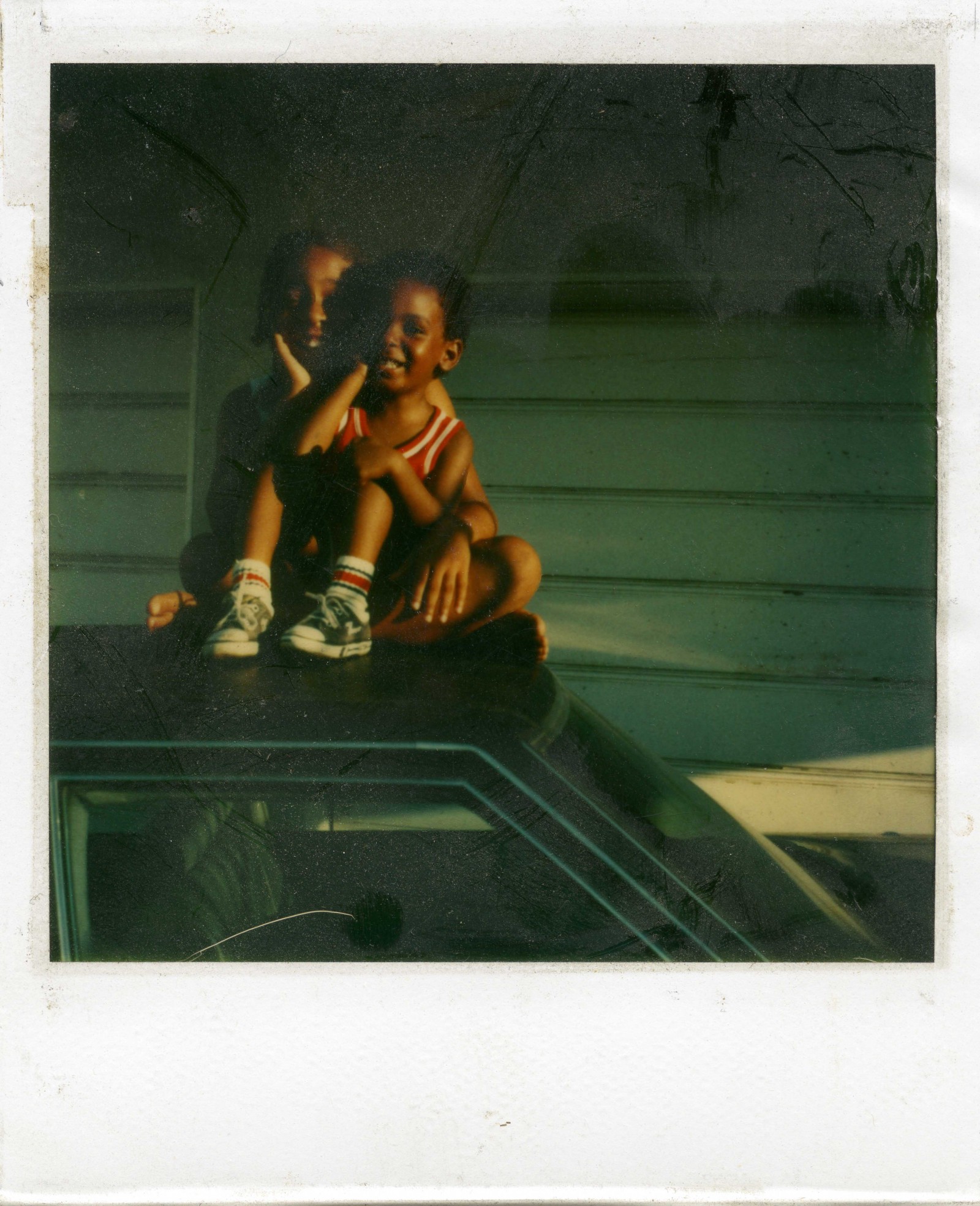

That’s me: Henry. And behind me is my sister Annie.

That was us the summer of ‘65, posing on the hood of mom and dad’s car. We were going to go on a road trip to the Grand Canyon. We’ve never been outside the state of Missouri, and our parents have been saving up for months before we had enough money to go. Our dad loaded up the car as my sister and I ran around him in circles, way too excited about the trip to do anything else. Once our mom huddled us into the car did we finally drive off, watching trees and houses zoom by. We sang songs and played I Spy as we drove on and on, laughing and making funny faces at the cars next to us. Mom was reading a book, her feet hanging out the window, while dad hummed a tune under his breath as he drove. Every now and again my dad would flick his eyes to us through the rearview mirror, to make sure that we haven’t disappeared. Annie and I would bounce in our seats, hoping that the sweeping landscape of the Grand Canyon would appear around the corner, but it never came.

This photo was taken 50 years ago, and that was the last time I ever saw my family. My mom was smiling back at me when an oncoming truck hit us. All I could remember was that the sky was raining of glass, and that we were flying.

I’ve bean dead for 50 years, but this is all I can remember.

Story by Sydney Druckman

TWO

It’s late July and the house is quiet and stuffy. Every window in the small house is opened, but the air is still thick and smells slightly of dust in such a way that is familiar to the home and somewhat comforting. The evening sun seeps through the windows and a gentle breeze brushes the curtains. I watch the clock that hangs on the faded kitchen wall above the sink, and a bead of sweat follows my spine down my back. The little hand lands on the six and and I bound up the stairs towards my little brothers room. I knock on his door before turning the knob and poking my head in. He’s sitting on his bed reading a book. I interrupt to tell him that it’s six o’clock as I do every evening.

Together, we race down the creme carpeted stairs clutching that railing in case our bodies can’t keep up with our fluttering feet. My brother reaches for the keys to the car and I push open the screen door that leads to the drive way. He opens the driver’s side door and slides the key into the ignition starting the engine, climbing back out after turning the radio on. He sets the dial to a station playing The Beatles which my mother likes.

We climb the hood of the the car and I fold my legs pulling the child onto my lap. His small legs stick to mine from the perspiration of us both but I don’t mind and neither does he. We sit on the roof of the car slightly swaying in unison to the music. We sit like this together, me and my brother, every evening waiting for my father to return from work.

My brother is wearing his Chuck Taylor’s and an old jersey. My father and him play basketball in the driveway with the old hoop nailed to the garage. It’s his favorite and if he’s finished his homework, they’ll play for hours. My favorite are these evenings. All day I look forward to sitting with my brother for a few minutes in silence beneath the crackling radio. I can feel his heartbeat on mine, occasionally synchronizing with the music, or speeding up slightly when our father’s car rounds the corner. Sometimes he traces shapes on my legs with his small fingers or fiddles with my shoelaces. He’s quite small and struggles to sit still for very long, but he remains patient while we wait. For our father he’d wait a lifetime.

Story by Makayla Minnes

THREE

Mallory was thirteen. In fact, she had just turned thirteen the week before. She had spent the entire week since campaigning to get her mother to allow her to babysit. “I will only charge two dollars an hour and that’s for both boys,” she said to her mother, as she sat in front of the mirror applying her makeup. “And the boys listen to me,” she reminded her. Just then, as if to help Mallory make her point, Chucky ran in yelling that Howie was hitting him.

Mallory took him by the shoulders and led him back downstairs. Jackie, Mallory’s mother, could hear her talking to the boys. A few minutes later, Mallory came bounding back into the room. “Howie was hitting him. I took a dollar out of his bank and put it in a jar in the kitchen. I said that any time they hit each other, I was going to take a dollar and put it in the jar. I told them we would send all that money they wasted to poor kids.” Jackie laughed. “Alright Mallory,” she said. “You’re hired.”

The boys were mostly good for Mallory. She made them do their homework after school and she made them help clean the house. They could play after all that was done. Chucky complained the most and did the least, but still, he pitched in.

That summer, Mallory watched the boys a lot during the day. Her mom got a new boyfriend and he came over on the weekends. They would ride out to the beach in his car. Mallory would always open her window all the way and turn her face into the warm, salty breeze. Chucky would sometimes hold her hair back for her.

One day, the five of them built a giant sand castle. It turned out so good that no one wanted to leave it. Jackie was mad at herself for forgetting the camera at home. But they did take one picture of that day. It was of the boys, Chucky and Howie, sitting on the roof of the car in their driveway after they got home from the beach. On the back of the photo, Jackie had written “Sand Castles.” This is Mallory’s favorite memory, the one she plays over and over again.

Story by Cara Long Corra

FOUR

It never fails to gut me every time I find a reminder. Packing the moving boxes today, I found this dusty Polaroid picture. He was such a sweet boy. He’s just a faded news story now, another lynching, dead before he turned 18. This smiling, sweet boy scared a big white man with a gun who shot him in the face. My baby brother, who would cry when Mama had to work when he wanted to be tucked in at night. My baby brother, whose heart grew bigger every time he found a stray and brought him home and begged and begged to be able to keep ’em, promising he’d take care of them and feed them and Mama would never have to do a thing. My baby brother, painfully shy, who kept his heart’s desires secret, who never had a lover and never will. My baby brother, who will live on only as memories of hugs and laughter and gentleness and kindness and beautiful brown skin and a heart so big it scared that white man with the gun so badly that he had to kill him. My baby brother, bloody and lifeless and black and buried and made into a boogeyman even though he was not yet a man. My baby brother, whose heartbeat I remember hearing for the first time at the doctor’s office with Mama. My baby brother, whose heart beat last the day before his birthday. My baby brother, whose name joined a long list of black boys and men lynched daily in AmeriKKKa. My baby brother, whose name has been forgotten by most, for there are too many other names piled on top of his and they continue piling up and up and up. My baby brother, who I miss and cry for every day, every time a new name is put on the top of the pile, every time life slices open another piece of my head, my heart, my skin.

Story by Christina Buck