Six stories

ONE

Curt’s been asking me to kick him out for a couple of days, now.

Honestly? I ain’t got the heart to. We usually get the old guys around here, head to toe in their polos and khakis, with their big red cheeks and wrinkly frown lines. They’re the kind of customers that tip with bible passages and scoff at your tattoos. But Walter… he was a different species entirely. Tipped what he could and dotted orders with “Please” and “Thank you”.

The first time Walter came to Martin & Russi, he had a gal on his arm. Thin, pale thing with a bony smile and a wobble in her step. His smile was bright, full creases in his cheeks when he bade the first “Table for two, by the water”. I figured this guy was some tourist tramping his way across Newport with the Misses and wanted a bite to eat.

It happened a couple of times: Walter and Mary at their usual spot on the corner, with the same order of black coffee and Hibiscus tea. Mary talked, and Walter laughed. Walter talked, and Mary smiled. They sipped their drinks, shook their heads, and sat in a long silence until the check came. Sometimes, Mary’d yank out the dead daisy leaves in the planter and pile’em on the ledge. Gave the gardener a run for his money, she did.

The last time I saw Mary had to be… ’82, maybe ’83.

Mary, my god, she was a sight. She dolled up something nice for an old gal: chiffon dress and a big, floppy hat, bug-eyed sunglasses and a ring for each finger. This time, she gave the call for a table and gave Walter a big, red kiss on the cheek. I gave them their usual spot and away they went, ordering their drinks and watching the waves roll when the laughter died. Their fingers danced along the edges of the table until they found each other’s palms and gripped lightly.

Walter hadn’t visited us in three years. Me being me… I figured he passed. He had to be an old guy, I thought: Mary’s hair was like snow, so he couldn’t have been far behind her.

Walter started coming again, last week. He swings by at opening, reserves a table for himself, just orders a coffee, and watches the water. He takes his good, sweet time sipping it too: drives everybody nuts on a busy lunch day. Sometimes, Walter picks the dead leaves from the planters and leaves them in a pile on the empty seat. Gives the gardener a run for his money, he does.

The last time I saw Walter had to be… ’84.

Heart trouble, doctor said.

Story by Melinda Sonido

TWO

He was a man of the ocean, I tell you.

I always heard the churning of black, murky water from the yachts and deep blares of horns. I heard light jazz mixed in with chatter of old men bragging about their boats named after their wives. I don’t know why I come out here so often- it’s so noisy, yet inspiring. The way the waves lap onto the sand reminds me of when I unplug from society and just write. I come here and always see the old man in the aviator sunglasses was always sitting at the white round table, sipping from his styrofoam cup.

“Can you hear it?” he said. I stopped writing and looked up.

“Hm?”

“Can you hear it?”

“Hear what?”

“The ocean’s song.” He paused and I could feel his glare through his shadowed sunglasses.

“What?” I asked.

“I bet if you really listened, you’d hear it too.” He turned to look out onto the field of boats, rubbing the styrofoam cup with his fingers. I squinted my eyes at him and turned back to my notepad when something plinks onto the ground and I reach down.

“Um, sir!” I yelled, but he kept going. I unraveled my fingers and saw a white skipping stone, which folded perfectly into my palm. I threw it into the sea and left. As I walked away, the skipping stone plinked on the surface of the water, and that’s when I first heard the stone playing the notes to the ocean’s song.

Story by Alena Nguyen

THREE

Some say he’s the fugitive owner of a fleet who used Filipino men to illegally fish off the Tanzanian coast. Some say he’s a Greek artist who is staring at the sea in the hope it will submit, with fear, to stand still for a painting. Some say he’s the estranged father of the café owner, basking in his son’s presence but fearing to get too close. Some say he’s a contractor who supplies brimming baskets of caviar and cloyingly sweet Moet to yacht owners with enough money to buy a whole fleet. Some say he’s even a yacht owner himself, and they click their tongues behind his back at his stingy purchase of one café au lait and one sablés de vanille.

Stingy, he may be, but certainly not disloyal. There are old crones who weave crab baskets with fishy hands who claim he’s been sitting in that white chair since they were young. And he wasn’t supple limbed and rich of hair like they were, oh no. The same lines on his sun-weathered face, the same salt and pepper hair, the same stomach pushing open that same beige shirt. Ask the propriétaire of the café and he’ll swear the exact same thing. That old man makes me my living, he says, even if he props it up with coffee granules and biscuits. The customers? They’ve made him an attraction as famous as the city itself, a mystery as big as the inside of the elegant yachts. His face on photos scattered across the globe; daubed in swirling, thick acrylics on years’ worth of easels; his description scribed in letters, in blogs, in notebooks, in travel guides, and even in a novel that the poor author tried to get him to sign.

Monaco is a place of constant change. The sea lures people away and carries people in. Moving homes make for a moving population, of new faces and old faces and all faces in between. But here, the rock against the tide, always turned towards the sea, staring out at something only he will ever know.

Story by Florianne Humphrey

FOUR

Sure, Charlie had a good life: he had graduated from the Kelley School of Business, married his high school sweetheart, with whom he had a daughter, and worked at a small but lucrative firm in San Francisco. But his wife Lindsay had been dead for over ten years, and the strained relationship he had with his daughter, Daisy, had dissipated from Christmas cards to scattered phone calls to absolutely nothing at all.

He still worked, but his office was undergoing changes: hiring young men with thin ties and ambition and an attitude that wouldn’t take “no” for an answer. Charlie wasn’t stupid enough to think he would stay on his team. Sure, he’d been around the company since its inception, but the new CEO – Daniel Chapman – was barely thirty-five and he had been laying off the older employees one by one. “It’s just that younger folks integrate better with the new software,” Daniel shrugged, as he gave a co-worker her two week notice: “I just need someone with spark in their eyes, not just a twinkle.”

A couple of weeks later, on a quiet April morning, Charlie woke up at 6 a.m, as he always did, and went straight for the docks. For the first time in forty years, Charlie skipped work to sit at the white garden chairs at a cafe called Le Printemps. He ordered a single cup of coffee, and looked at the rows and rows of yachts, gently bobbing in the water.

He took out two letters from his pocket: one with “Letter of Resignation” typed on the back, and the other, addressed to his daughter Daisy. A change was needed, Charlie thought. He’d visit Daisy in Philadelphia, if she let him.

Story by ‘In’

FIVE

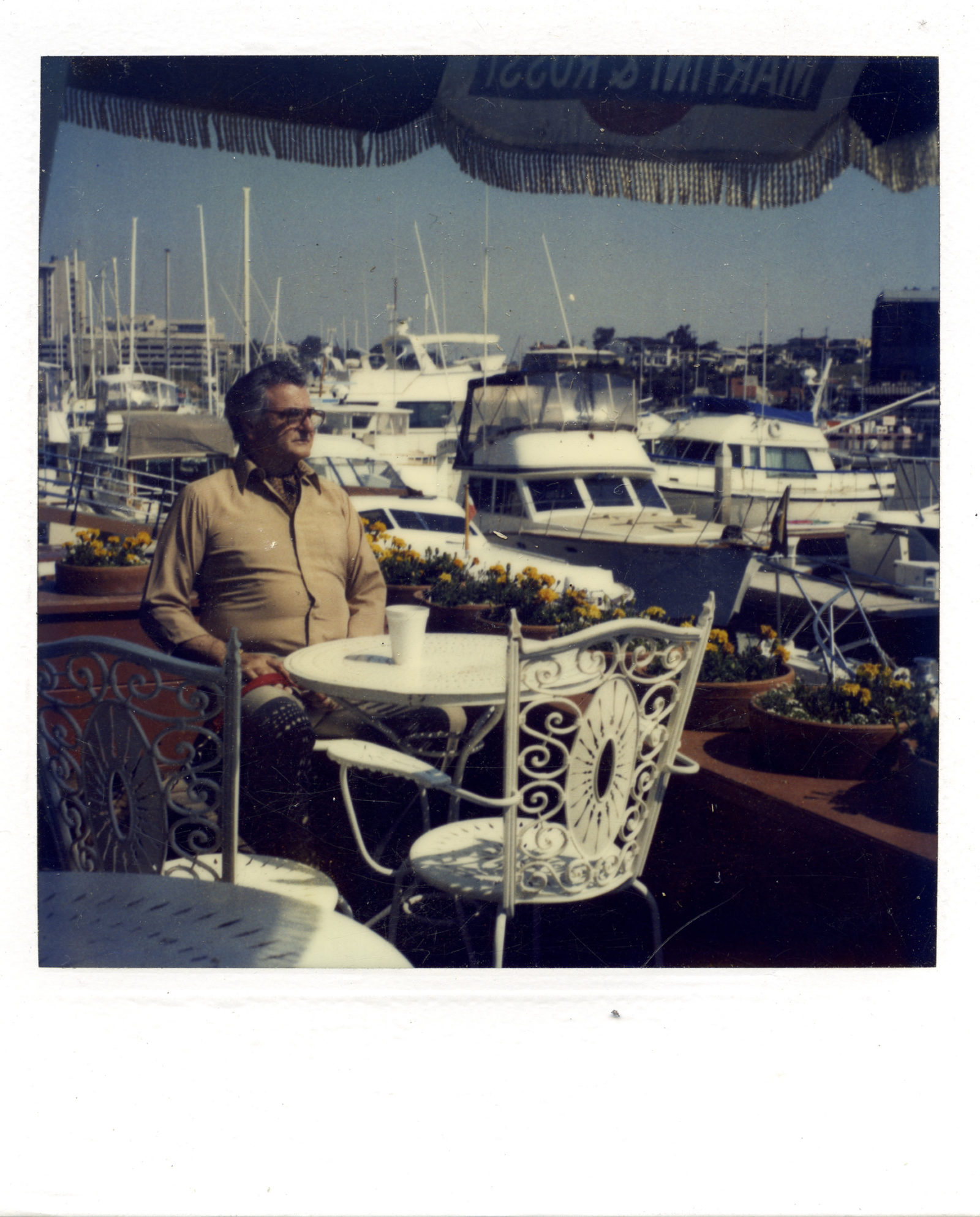

I remember coming here with my father when I was just a little boy. It was a small coffee shop on the edge of the harbour. We used to come here after a long day of sailing just off the coast of Southern Florida. Everyone knew us there, they even had our orders memorized. I’d always get a hot chocolate and my dad would get Cuban Coffee. I never understood why though… he was born in Canada. After we would get our drinks, we’d sit in the corner so I could see all the boats that were coming into the harbor. My dad would ask me about my favorite parts of the day’s trip, and then where I wanted to sail to next. We always had so much fun together. One day he surprised me with a Polaroid camera for my 12th birthday. He knew how much fun we would always have together so he wanted to help me have those memories last longer. I would take so many pictures! They ranged from seagulls flying against the wind, to the islands we would dock at. I even have pictures of a lot of the boats that we sail past. In my room, I tape all the pictures in my wall to make a collage of my travels and experiences that I had. The picture I have here I took of my dad the last time we went sailing together. It’s been 40 years and I still remember those amazing times we had together.

Story by Evan Scolnick

SIX

Unlike Marcos’ own relationship with time, the years had treated Cafe del Mar well. The seats were the same shade of steely white, the potted daisies and lilies blooming like they had been when Marcos first saw the joint, back in 1954 or ‘55, when it wasn’t a chore to sit down, when his hair was short and tight and flaunted a noticeable lack of gray, when women in long green skirts would approach him, rubbing their hands over his naval uniform, smoking cigarettes and drinking stiff drinks, never concerned with learning names because everyday a new name was presented while an old name was lost, so why even remember in the first place?

At least the coffee was still shit. It made Marcos thankful, really, that the coffee was just as bitter, swimming with grounds, always a degree too hot or too cold. In this case, no change was a negative, which to those Marcos’ age was almost like a sign from God.

For him, change, the progression of time, the arrow of life had done little more than kick him in the balls and grey his hair. Women no longer approached him, just one puff from a cigarette sends him careening into a hacking fit that sounds like the deck guns he used to listen to, watching the locals strut around the pier in neon clothing, making them look like the tropical birds he’d seen during the big one.

Coming back here was not a good idea. The damned thing about change, is that it makes you want what was before. War was hell, and yet all he could think about, all he wanted was to be back there on the deck of his gunship, yellow sun beating down on his shirtless body that hadn’t yet been taken by fat.

Change. Marcos didn’t know how much change he had left in him. Change, like the coast, receding and gaining, never as it once was, fluid and unwritten.

Change. At least the coffee never changed.

Story by Mason Ahrens